This month our blog features a guest post from Valerie Worth-Stylianou. Valerie is a Senior Tutor at Trinity College and the Mellon-TORCH Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the University of Oxford. This blog post features an in-depth look at one of the RCOG’s early printed books which featured at the recent Knowledge Exchange workshop hosted by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists in partnership with The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities and the De Partu History of Childbirth Group.

—

The Library of the RCOG holds a rare copy of the first edition of the Observations of Louise Bourgeois (1563-1636), midwife to the Queen of France (Marie de’ Medici, 1575-1642).

The portrait was engraved in 1608 by Thomas de Leu, a court artist. Her status as royal midwife is indicated by her velvet collar, velvet cap and gold cross. Her age (forty-five) suggests her experience.

The four lines of poetry pay a conventional compliment (‘In this perfect portrait, the limits of painting/ Are clearly evident to our eyes today/ Because we see only the representation of the body/ Not the mind that is admired as a masterpiece of creation.)

As far as we know, the book, which appeared in Paris in 1609, was the first published work by any midwife. Bourgeois authored two more volumes of Observations, in 1617 and 1626, and in 1635 also published a collection of cures she had used throughout her working life. The Observations were immensely successful, being reprinted regularly in France for some 50 years, and translated into German and Dutch. Extracts were lifted and put into English in the very popular anonymous compilation entitled The Compleat Midwifes Practice (first edition, 1656). When the French-American artist and sculptress also named Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010) discovered her namesake, it inspired her to produce several colour plates.

Apart from their place of honour in the Library’s collection as the earliest printed work by a midwife, the Observations give fascinating insights into an early modern midwife’s thoughts and practices. Bourgeois reckoned that in the course of her career she attended over 2,000 deliveries in and around Paris, and her approach – as the title suggests – draws on her personal experience, often using case histories as the means to understand more general principles of diagnosis and treatment. I have selected a few short extracts from the second chapter of the 1609 volume, on the subject of miscarriages and premature births, to show how Bourgeois’ approach is refreshingly personal. The translations into English are mine, and I’ve tried to convey something of Bourgeois’ individual style, suited to a reflective work published in the vernacular rather than a learned medical tome in Latin.

In this first extract, she is very interested in the association between a pregnant woman’s emotional state and her physical wellbeing. In particular, she proposes (echoing many doctors, and the celebrated surgeon Ambroise Paré, 1509-1590) a close correlation between anger and miscarriage. She believes anger disturbs the humoral system of the body, affecting the blood and interrupting the foetus’s development. Because she is writing primarily for student midwives or a readership without medical training, she often draws comparisons with natural or commonplace objects to make her accounts clear and vivid, as here where the products of the miscarriage are ‘formed like a duck’s egg’:

‘The most frequent reason for a woman to give birth [prematurely] is anger, which sometimes occurs while the child is being formed … So I saw a woman who believed she was pregnant and carried her burden for four and a half months, whereupon she suffered pains and delivered a dense membrane, thicker at one end than the other, formed like a duck’s egg, and containing reddish water and many white strands, with three swellings like small grains of crystal, the one higher up being larger than the other two, which were of different sizes. I therefore asked the woman whether, when she thought she might have become pregnant, she has perhaps experienced fear or anger. She told me that she had been extremely angry and troubled just after she had missed her period and had already experienced some changes, such as trembling and nausea. From this I judged that her anger had occurred at this time, according to what Paré notes in his Book on Generation, where he speaks of the three swellings that become the heart, liver and brain.’

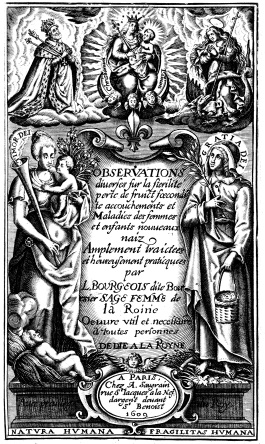

English translation of the title page:

Diverse Observations on Infertility, Miscarriage, Fertility, Childbirth and Illnesses of Women and of Newborn Infants. Fully discussed and successfully practised by Louise Bourgeois, also called Boursier, midwife to the Queen. A work useful and necessary for everyone. Dedicated to the Queen.

Paris, printed by A. Saugrain, rue St Jacques at the sign of the Silver Ship, in front of St Benoît. 1609.

With the King’s privilege.

In another extract from the same chapter, where she is examining the causes of miscarriage, she relies on her own extensive experience to evaluate the significance of nature versus nurture. Her conclusion that countrywomen’s daily activities prepare the body for pregnancy and birth is similar to much modern thinking: see the RCOG’s statement number 4, January 2006 on ‘Exercise in Pregnancy’:

‘I used to be astonished to see that right up to the day of giving birth, sometimes to twins, countrywomen would lift bundles of hay and carry them on their head, without miscarrying. But when I pondered on the reason why, I realised they have been used to this activity since they were young. So since childhood their ligaments have been stretched when their wombs were empty, and they had become strong through their work. If other countrywomen, who had grown up as children in the town before returning to live in the country, tried to work in the same way, I observed that they soon miscarried, which leads me to conclude that nurture is more important than nature in this regard.’

For those interested in finding out more, I warmly recommend Wendy Perkins’s study: Midwifery and Medicine in Early Modern France: Louise Bourgeois (Exeter: 1996). And an annotated translation into modern English of all three volumes of the Diverse Observations (edited by Alison Klairmont-Lingo and translated by Stephanie O’Hara) is due to be published in 2016 by Iter Inc. & Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, University of Toronto.